Naming and Blessing

Researcher: Prof. John Rodwell*

Naming in science captures a unique moment of encounter between the keen eye of the enquirer and a creature previously anonymous and brings it before the scientific audience as something now known. But such an endeavour readily becomes hubristic, the attentive eye moving from delight and understanding to something more predatory, making some claim of ownership of biodiversity in the ordering of classifications and the precision of naming. The ‘Naming & Blessing’ project will explore tensions between such naming and the experience of God’s free grace promised in Christian notions of blessing. It thus revisits contrasts between literal interpretations of ‘dominion’ and more nuanced understandings of the common home we share with the rest of Creation.

To the patristic and medieval minds that searched for understanding of the natural world, the Christian reality of the imperfection of humankind was determinative. One expression of this conviction was that, in the Fall of Adam, a privileged encyclopaedic knowledge of creation had been lost. To restore some intellectual order to the wildness of nature thus became an urgent quest.

Collections of the wonders of nature - the weird, the ingenious, the inexplicable – were a by-product of the discoveries that accompanied exploration of the natural and colonised world. Such Wunderkammer burgeoned in the Enlightenment, promiscuously assembling discoveries from exotic places around the globe. Like the medieval bestiaries before them, the Wunderkammer was a place where uncritical respect for inherited ideas, folklore and an omnivorous appetite for oddity jostled together. A crucial step in the systematising of knowledge about such diversity in the natural world was the development of a standardised method for sorting, classifying and naming plants and animals. Names progressed from informal tags, through narrative and ever-more cumbersome descriptions to the neat binomials of Linnaeus.

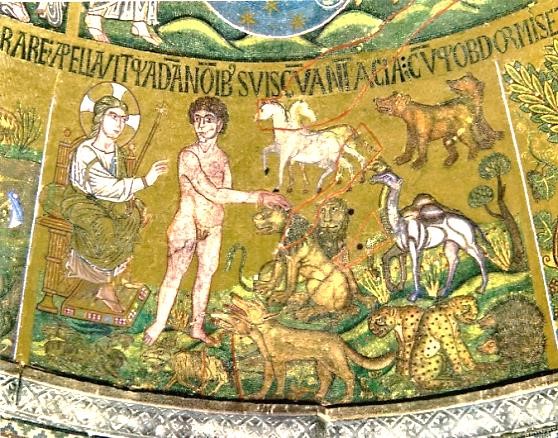

The science which we practice, classifying and naming plants and animals, may clearly serve not only our delight but also apprehend these creatures for use, in consumption and commodification - from necessity, by greed, for fun, through carelessness. Within such a frame, the permission to name, so dramatically expressed in that Judaeo-Christian creation story where the animals are paraded before man and ‘whatsoever he called it that was its name’ (Genesis 2, 19), this takes on a particular force, as if it were part and parcel of some claim of ownership.

It has been thought that, in some kinds of religious traditions, the spoken word is given power to become an operative reality with a capacity to conjure up and effectively possess the named thing. In fact, however, in the Jewish scriptures, although the act of naming is expressed in quite a variety of ways, ideas that it bestows dominion, affects the essence of named things or somehow constrains the bearer of the name, all these are misreadings. Rather, naming is about discernment, recognising an essence and marking a difference that is already there. Thus may we see a delight in naming that shifts an environmental ethic from something that is entirely anthropocentric to one that credits the diversity of nature with an existence free of our own and some measure of intrinsic value. Moreover, in the Judaeo-Christian tradition, words gain their power by the recognised authority of the speaker and naming can be seen as a ‘performative utterance’ whose power operates only within a particular realm of use. It is such a dramatic interpretation of blessing which will provide a critical tool for re-examining the whole process of naming.

The research will involve literature survey; engagement with Wunderkammer, scientific collections, gardens and their curators; interviews with artists, writers, actors, preachers and pastors concerned with performative utterance; and reflection on field experience of encounter and identification of plants and animals. This is unfunded research with periodic application for travel and subsistence.

John Rodwell has worked as a professional scientist and Anglican priest together for over 40 years. Until 2004 he was Professor of Ecology at Lancaster University, establishing an international reputation in research and database development with a long publishing record. He now works independently providing expert advice for environmental agencies and NGOs in this country and elsewhere in Europe, most recently for the European Commission, the European Environment Agency, Defra and the National Trust. At LTI, he has originated the ‘Belonging & Heimat’ project, co-edited At Home in the Future (LIT Verlag 2015) and contributed to the ‘Big Society – Bigger Nature’ conference. He is especially interested in the interface between nature and culture and ideas of memory, place and well-being, contributing to Faith in Science (Routledge 2001), Knowing the Unknowable (I.B.Tauris 2009), Objects of Curious Virtue (Walker Fine Arts 2010) and the Practices of Happiness (Routledge 2011). A Canon Emeritus of Blackburn Cathedral and priest at Lancaster Priory, he works in the north-west and across Britain, through preaching, retreats and community projects to explore our relationship with our fellow creatures and the nature in which we together find ourselves.

The image shows God giving Adam the privilege of naming the animals of Creation in a mosaic from San Marco, Venice.