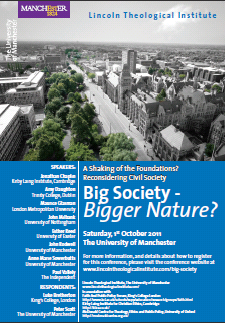

Big Society —

Big Society —

Bigger Nature?

Saturday 1st October 2011

The University of Manchester

Samuel Alexander Building (no.67 on the campus map), room A113

10 am (coffee from 9.30 am) – 4.15 pm

Conference chair: Peter M. Scott, Director, Lincoln Theological Institute, University of Manchester; +44 (0)161 275 3064; peter.scott@manchester.ac.uk

Conference administrator: Hannah Mansell +44 (0) 161 275 3319; hannah.mansell@manchester.ac.uk

So far, the question of the relationship between the “Big Society” and a wider Nature has not been raised. This day conference addresses this lack through the consideration of critical questions such as:

- How does the “Big Society” acknowledge its dependence on a wider Nature?

- How does the Big Society encourage resistance to the anti-ecological practices of the modern state?

- Are we free, as humans, to volunteer Nature as a participant in the Big Society?

- What is the relationship between the Big Society, civil society and economic markets?

- Does attention to civil society serve to obscure the moral responsibilities of the modern state?

- Does Citizenship trump participation in the Big Society?

- The Big Society as the Good Society—what is the relevance of Catholic Social Teaching to the debates on the Big Society?

SPEAKERS:

Jonathan Chaplin (Kirby Laing Institute, Cambridge)

Can ‘nature’ tell us how big society should be?

For the latest by Chaplin on the Big Society, click here.

Influential streams of modern Christian social thought often appealed to the idea that the normative design of society should reflect the imperatives of ‘nature’ understood as ‘created order’. In Catholic thought, this generated the proposal that a range of ‘natural communities’, as well as other associations each pursuing a supposedly ‘natural’ telos, should be protected by, and should delimit the authority of, the state. In Reformed thought the parallel notion of ‘creation-based social structures’ served the same purpose. Both yielded injunctions regarding how ‘big’ society should be in relation to the state; these injunctions substantially informed Christian political practice in 19th and 20th century Europe and beyond. Yet traditional formulations of these ideas often tended towards essentialism and authoritarianism. In time, the very idea that ‘nature’ could serve as a source of normative instruction for contemporary societal orders was abandoned by most Christian social theorists. Yet the current ecological crisis is delivering stern lessons about the ‘natural’ limits on the activity of human social institutions. In the light of this, this paper revisits the idea of a ‘natural’ design of society, exploring whether it may yet yield necessary insights, not firstly regarding how ‘big’ social and political institutions should be, but rather regarding the irreducible and complementary human goods such institutions might be construed as facilitating.

Amy Daughton (Trinity College, Dublin)

Climate Justice -- the Bigger Society

The emerging tradition of thought on the Big Society emphasises the policy opportunities of nature: new energy markets, the goal of a zero-waste society, the social capital of green spaces. To an extent this recognises the dependence of national interests on the global environmental context. However, a valuable critical voice is provided by the rhetoric of climate justice over climate change (e.g. the MRFCJ). This approach emphasises the capacity of societies to protect those who are most disempowered. By approaching climate questions in terms of human rights, not exclusively as policy options, the Big Society is effectively called to be much “bigger” in its recognition of the other.

Maurice Glasman (London Metropolitan University)

John Milbank (University of Nottingham)

Esther Reed (University of Exeter)

Entitlement and the Big Society: Three Reasons for Rethinking the Moral Responsibilities of the Nation State

Christian political theology is unwise to allow proper concerns about the well-being of civil society substitute for questions about the moral responsibilities of the nation state. Cameron's Big Society is seen through the lens of Peter L. Berger, Richard John Neuhaus and Michael Novak (eds), To Empower People: From State to Civil Society (1977) in which civil society is acknowledged to be a political battleground wherein the major players want to shift public attention away from the responsibilities of government in achieving greater social equality.

John Rodwell (The University of Manchester)

Attending to the Snake

On many views, our creatureliness is seen as subverting the possibility of civilised behaviour, and ‘the wild’, inside us or out, is something which we wrestle with or stand against. In the Judaeo-Christian tradition, attending to the snake in the creation stories is even blamed for destroying our aboriginal innocence as the obedient handiwork of God. Yet, acknowledging our companionship with the rest of what has been made, as an integral part of the household or oikos of creation, precedes our loyalty to the polis. In our religious practice, in negotiating human well-being, in ensuring that the state of the environment is not simply an instrument of socio-economic benefits, we need to find our rightful place in a bigger nature as the basis for our commitment to any big society.

Anne Marie Sowerbutts (The University of Manchester) & Paul Vallely (The Independent)

Speaking up for the common good: Catholic Social Teaching in the context of debates on the Big Society

With its idea of the Big Society, the Government is seeking to impact and reconfigure civil society in this country. Catholic Social Teaching (CST), with its in depth thinking on the nature of the human person and society, is a useful resource to critique those proposals. The Big Society emphasises collective action and responsibility at a local level. These are laudable aims and find resonance with CST. Catholic Social Teaching, however, will always champion the common good, which involves a concern for all in society but particularly the vulnerable. Achieving the common good in a society requires consideration of other elements of CST such as human dignity, solidarity and subsidiary as well as the roles of the state, the market, freedom, accountability and the role of the church.

RESPONDENTS:

- Luke Bretherton (King’s College, London)

- Peter M. Scott (University of Manchester)

ORGANISED BY:

Lincoln Theological Institute, University of Manchester

in association with

- Faith and Public Policy Forum, King's College London

- Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics, Cambridge

- McDonald Centre for Theology, Ethics and Public Policy, University of Oxford

ATTENDANCE & COST:

If you wish to attend, please send a brief e-mail to the conference administrator, Hannah Mansell (+44 (0)161 2753319) hannah.mansell@manchester.ac.uk

Any special needs should be communicated to the administrator at this stage.

For staff and postgraduate students at the University of Manchester, the conference is FREE. However, you MUST register with the conference administrator, Hannah Mansell.

For postgraduate students at other universities in the UK, the conference is FREE. However, you MUST register with the conference administrator, Hannah Mansell.

Otherwise, there is a nominal charge for attendance, which includes lunch, of £10.00. Preferably, this fee should be paid using the university’s online payment system.

DIRECTIONS:

For information on how to get to the University, please click here.

ACCOMMODATION:

If you require somewhere to stay, please click here to access details of local hotels, variously priced.

FURTHER INFORMATION:

The promotion of the theme of the “Big Society” by Prime Minister David Cameron continues to provoke much comment, including contributions from theologians. The “big society” opposes the “big state” and stresses voluntarism and localism. It is the big idea that supports self-help, mutuality and local accountability. It takes heart from the voluntary activities already being undertaken by a range of faith groups.

Although there has been some appreciation of this promotion of civil society much of the comment has been negative. Moreover, as the spending cuts being prepared by the UK coalition government become a reality, the “Big Society” has come to be identified with an attempt to obscure these cuts and compensate for their effects.

The current political argy-bargy obscures the fact that there are important changes going on within civil society and the relation of civil society with other sectors. Part of the historical argument over civil society has been whether or not it is a creature of the state or the economy. Behind this is the vital issue of civil society as a source of ‘political’ authority: is political authority to be sourced not to the constitution of a society by its state but rather the self-constitution of a society through its basic practices, communities and associations? Additionally, how does this question relate to the distinctions that we commonly make between Left and Right, or is this distinction losing its salience?

This conference takes seriously the decomposition and recomposition of civil society and the resulting implications for the foundations of our present society and its various sectors. Whether we are at an historical juncture beyond which the future must be very different from the past remains unclear. Nonetheless, there are clearly profound tensions or contradictions emerging: the resources required to support an ageing population and the impinging reality of anthropogenic climate change by themselves suggest that a bold response will be required.

Not least, the most recent developments that have most substantially changed Western societies have been movements or activities in civil society. The labour and women’s movements and the globalisation of finance and communication have been, and have unleashed, powerful forces that shape our present societies. Also, largely unvoiced in the current debate are the pre-political allegiances which locate our responsibilities to society within an awareness of our creatureliness and that question the notion that the environment can be simply volunteered in support of socio-economic well-being. Moreover, it is likely that the pressures of future shocks will be felt by groups and communities in their localities and neighbourhoods where some of the important negotiations will have to be undertaken and compromises made. It is timely, then, to take a critical look at civil society in order to grasp its capacity, resilience and sustainability.

As vigorous actors in civil society, religious communities—including churches—have a stake in the health and vitality of civil society, the relationship between economic interests and non-economic associations, and the relationship between civil society and the state. Seizing this timely moment, therefore, four religious/theological research institutes are supporting this effort to explore these issues from a range of perspectives and disciplines.